The importance of photos

- Jun 17, 2015

- In Features

Photographs play an important role in everyone’s life – they connect us to our past, they remind us of people, places, feelings, and stories. They can help us to know who we are. For people who grew up in children’s institutions, photographs are especially important – sadly, this is because for so many people, the photographs most of us take for granted, don’t exist. The Senate’s ‘Forgotten Australians’ report (2004) asserted that ‘The lack of photographs and mementos is felt keenly by care leavers … Photographs are a tangible link to the past, to their lost childhood’ (p.255).

One woman’s submission to the Senate inquiry reflected on how photographs helped her to connect to her identity and her past:

Years later I visited every home where I lived and took photos so that I could validate to myself that ‘yes, this place really does exist’ and I remembered what my life was like when I lived there (Submission no.470).

Photographs, even of buildings, can be vital memory cues for Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants. For some people, images of Homes are as important and as treasured as some people’s family albums. On the Find & Connect website, our state-based historians sourced as many photographs of children’s institutions as possible – the aim was to have at least one photograph for each entry about a Home.

But despite the team’s best efforts, it hasn’t always been possible to find an image for every Home. But this doesn’t necessarily mean that there are no photos ‘out there’. From time to time, people contact us to let us know about the existence of photos, so these images can be made available to the wider public.

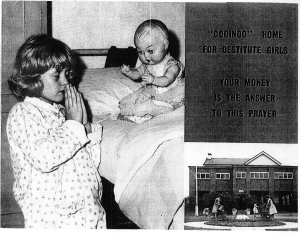

Last year, a woman in Queensland got in touch with us at Find & Connect when she noticed that we had no image for Cooinoo Home for Destitute Children – she and her sister had been there as children. She very kindly sent us a copy of a flyer produced to raise funds for Cooinoo, so that we could add it to Find & Connect.

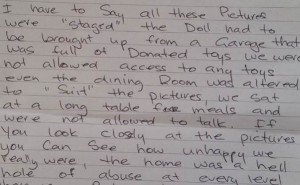

When she sent us the copies, she wrote about the pictures:

I have to say all these pictures were “staged” – the doll had to be brought up from a garage that was full of donated toys. We were not allowed access to any toys, even the dining room was altered to “suit” the pictures. We sat at a long table for meals and were not allowed to talk.

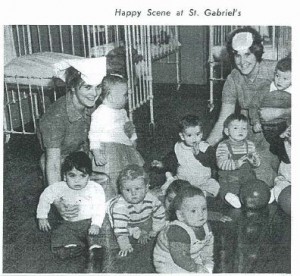

The majority of photographs on Find & Connect that feature children and young people are quite obviously staged – it was common for institutions to use photos of ‘orphans’ in their publicity or fundraising materials, like this picture from St Gabriel’s Babies’ Home in Balwyn, VIC.

photograph in the Mission of St James

and St John’s annual report for 1963.

It is important to know the context behind these photos – it tells us that what we see in these images is not likely to be a candid snapshot, giving an accurate representation of daily life in a children’s Home. Rather, these images show us how the institution wanted itself to be seen by people on the outside.

In 2015, it’s rare for a photograph to be taken of a child (let alone published) without a parent or guardian signing a permission form, giving consent. Did the children in publicity shots from the 1950s consent to be photographed? And was it ‘informed consent’?

At a workshop in 2010 organised by the Who Am I project, there was spirited discussion about this notion of consent in historic photographs from children’s Homes. Care Leavers who attended the workshop were adamant that children in these types of photos could not be said to have consented:

They’re children, they’re not in a position of power …

In those regimes, homes and orphanages in the 40s and 50s, you’d be in trouble if you didn’t look at the camera!

It’s true! We were told to smile!

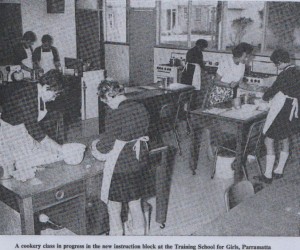

Over time, it became less common for care providers and institutions to feature the faces of children and young people in the photographs they used in their annual reports or other publicity material. From the 1950s onwards, annual reports produced by government departments tended only to show children from behind, or from such a distance as they were difficult to identify.

new instruction block at the Training School

for Girls, Parramatta, c. 1970 (Children’s

Welfare Department NSW, Annual Report, 1970).

If the photographs are of residents of juvenile justice institutions, like Parramatta Girls’ Training School in NSW, or Winlaton in Victoria, issues of consent, and of making images of the residents available in the public domain, are even more problematic.

On the Find & Connect website, we do include photos that feature children and young people, and some of them would be identifiable. We only publish photos that are already in the public domain (for example, they are already online through state libraries or museums, or they were published in newspapers). When we feature these types of photos, we do not publish the names of the children without prior approval of the persons named.

We publish some images that contain children on Find & Connect because our aim is to improve access to historical material and to raise awareness about the history of children’s institutions in Australia. This history isn’t just about buildings, and the organisations that ran them – the children and young people who lived in these places need to be written back into history. But the public good of improving access to photographs has to be balanced against the importance of personal privacy. On our About page, we urge people to get in touch with us if they have any concerns about a photo on Find & Connect.

jenny

June 19, 2015 1:43 pmMothercraft Nurses are a wonderful source of photographs. The St Joseph Babies Home at Broadmeadows operated from 1901-1975 (the mothercraft nurse training school operated from 1931 to 1975). During this time, hundreds of women completed their training, some staying on to work at the Home and some becoming Sisters of St Joseph. Many of the nurses took photos of the babies and toddlers they cared for. In 2007, the Heritage and Information Service of MacKillop Family Services undertook a very special project with former mothercraft nurses where they were asked to add their photographs to our historical records collection. These photos have now be indexed and digitised and are made available to people. For many people who grew up in Homes or separated from their family, this will be the first time they see a baby or toddler photo of themselves. But more than this, in many instances the person has been able to meet or make contact with the nurse (where she is still living) who looked after them.

Cate O'Neill

June 19, 2015 3:52 pmThank you, Jenny – there’s more information about MacKillop Family Services and its records on this page: http://www.findandconnect.gov.au/ref/vic/biogs/E000691b.htm

We had a former mothercraft nurse from the Presbyterian Babies’ Home contact us at Find & Connect – she ended up depositing her photos of staff and children from 1974-75 with Connections UnitingCare so that they could be more accessible.

The photos taken by mothercraft nurses are indeed an incredible resource.

Frank Golding

June 19, 2015 7:48 pmA great resource. I wonder how many of the babies in these precious photos have been identied and how many of the ‘subjects’ have been able to be contacted to inform them that their photo as a baby can be supplied to them? I hope it’s many, but I know that may not be possible.

Frank Golding

June 18, 2015 2:15 pmBallarat Child & Family Services (CAFS- which inherited all the old records, including photographs from the old Ballarat Orphanage) always lays out the old photograph albums at reunions so that former residents can look through them, not only to find photos of themselves but to help CAFS identify those children who have not yet been identified. In all the many years CAFS has done this, there has not been a single complaint. No one sees this as a breach of privacy. On the contrary, this is such a popular activity that it’s sometimes difficult to get past the queue. Browsing the photo albums is a fun activity. I’ve been to many school reunion where class photos are hung on the walls. Never a complaint!

Mike

June 17, 2015 11:51 amGreat post – thanks Cate!

Cate O'Neill

June 17, 2015 10:40 amLast weekend in the Bendigo Advertiser there was a wonderful story about photographs taken in the 1960s by mothercraft nurses at Berry Street Babies’ Home and Hospital in Victoria.

Sue had never seen a photo of herself as a child. When she approached Berry Street seeking more information about her childhood, Sue discovered that the Berry Street Heritage Collection contained 29 photos of her. (Apparently there were so many images because she had featured on the back of a box of Berry Street matches – a fundraising idea that strikes me as odd – pun intended, sorry.)

You can read the story here.