Six years ago today, the Australian Parliament issued an apology to Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants. Six years is a long time – in Canberra alone, so much has changed since that day in November, 2009 when (then-Prime Minister) Kevin Rudd issued his apology, followed by the moving words from (then-Leader of the Opposition) Malcolm Turnbull.

I remember 16 November 2009, standing at the back of an auditorium in the State Library of Victoria, where a couple of hundred people had gathered to watch the Apology live on a big screen. For some reason, the ABC chose to cut off its broadcast before the ceremony in Canberra had finished, and those of us watching in Melbourne missed out on hearing Malcolm Turnbull’s speech. It was only later, back in the office that I got to hear his words – and like so many people, I was struck by the devastating emotion and the compassion of Turnbull’s speech. Maybe he was free to speak with that much passion and honesty because he’s NOT the prime minister, I remember saying to my colleagues when we reflected on the differences between Rudd and Turnbull at the Apology. The ending of Turnbull’s speech had echoes of another famous piece of Australian oratory, Paul Keating’s ‘Redfern speech’ from 1992. Turnbull concluded by saying:

For those of you who have suffered decades of grief, haunted by your childhood, emotionally paralysed and unable to move forward, today I hope you can take the first step forward because you are not to blame. It was governments, churches and charities that failed you and for this, we are truly sorry.

In the lead-up to the 2009 apology, Malcolm Turnbull had made a visit to the Care Leavers of Australasia Network’s (CLAN) National Orphanage Museum. (Turnbull is one of several members of parliament who are Patrons of CLAN.)

It was at the Orphanage Museum that Turnbull came across Peter Hicks’ suitcase and the story that it told. He spoke about it in his speech on 16 November:

The inside lid of the suitcase was plastered with the marks of old sticky tape Peter had used to attach, very carefully, the lists of the contents of his suitcase – a pair of socks, a pair of underpants, a pair of shorts, a shirt – this was all his worldly possessions.

Peter Hicks was given the suitcase at the age of 4, and it was in this suitcase that he packed all his things when once a year he was sent off from the children’s Home to stay with ‘holiday parents’ at Christmas. Peter stayed with same family every year and maintained a close relationship with them, that extended beyond his time in Homes. (You can read more about Peter Hicks in the transcript of Turnbull’s speech which follows below.)

Turnbull’s apology speech made an impression on journalists, not to mention on the people who were gathered at Parliament House to hear it. One journalist wrote:

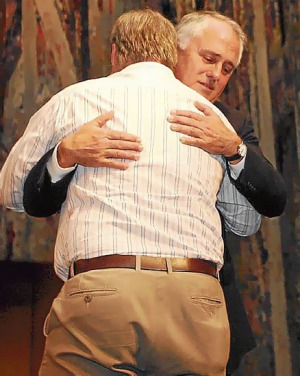

When Turnbull spoke, nobody booed or turned their backs [in contrast to Brendan Nelson’s words as Opposition Leader following Rudd’s apology to the Stolen Generations in 2008]. Instead, people wept and one man – Peter Hicks, the boy with the suitcase – rushed the stage to hug Turnbull as he recounted the tragedy of Peter’s childhood.

The Parliament of Australia website has a video of Rudd and Turnbull’s speeches at the Apology in 2009. On this anniversary, I urge our readers to watch the whole video and listen again to the apologies offered by the Australian government, and reflect on what this momentous event meant and means to Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants.

It is indeed a shame that the 2009 Apology is one of Kevin Rudd’s ‘less remembered achievements’ and that this momentous and long-awaited event is not more prominent in the national consciousness. Undeniably, the level of public awareness today about the history of children’s institutions in Australia has increased since 2009, and there are more services and support available to people who grew up in Homes. But the anniversary of the apology is a time to reflect not only on what has been achieved, but also on the work still to be done.

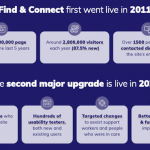

The Find & Connect web resource is one concrete measure that came out of the 2009 apology – the website is a public knowledge base about the history of ‘care’ around Australia and provides information about the surviving records that are dispersed across a range of government and non-government organisations. At the national conference of the Australian Society of Archivists in Hobart in August 2015, a number of speakers referred to the systemic failings in our archival and recordkeeping systems. Until we can address these failings, and transform our practices around recordkeeping and providing access to vital information, Forgotten Australians and Former Child Migrants – who rely on records to address problems relating to identity, memory and accountability – will continue to be disadvantaged.

Transcript of Malcolm Turnbull’s speech, 16 November 2009:

Thank you very much Mr Speaker and Prime Minister thank you for your speech. The motion has the unqualified support of the Opposition.

Now the Prime Minister recognised my fellow Members of Parliament and diplomats and other members of the great and the good but I just want to say today I’m talking to all of us, to all of you, the good, to whom so much wrong was done.

Today is your day. You are here today in your hundreds, representing hundreds of thousands of survivors of childhoods stolen and abused.

You were abandoned and betrayed by governments, churches and charities.

Thousands of children, some of you taken from the other end of the world, were placed in institutions – with many names; orphanages, farms, training schools, gaols – called “homes” although most were as far from “home” as one could ever imagine.

Those of you who were child migrants were part of a deliberate and calculating policy of many governments to bring children from Britain and Malta to populate the Empire with “good white stock.”

Arthur Calwell, the Australian Immigration Minister at the end of the Second World War, planned to bring 50,000 orphans to Australia – mercifully his target was never reached.

Churches and charities competed to gather up orphans of their own denomination.

And as government ministers and bishops and chairmen of charity committees congratulated themselves on their generosity and kindness, too many of you were left in the care of people who abused you, who beat you, who raped you, who neglected you cruelly.

And as we have seen from your own testimony, too often if you dared to complain, you would just be beaten again.

Some of you were lied to, told you had no family. That your mother was dead when she lived. That you had no brothers and sisters when you did.

Already stripped of your own sense of identity, your own childhood, many of you were just given a number.

What a cruel and bitter absurdity it is, that this system of “homes” reinforced and made worse every vulnerability and frailty of its inmates.

Today we acknowledge that, already feeling alone, abandoned, and left without love, many of you were beaten and abused, physically, sexually, mentally – treated like objects not people – leaving you to feel of even less worth.

Today we acknowledge that with broken hearts and breaking spirits you were left in the custody – we can hardly call it “care” – of too many people whose abuse and neglect of you, whose exploitation of you, made a mockery of their claim that you were taken from your own family “for your own good.”

Today we acknowledge that your parents who, ground down by poverty, surrendered you into the hands of those who claimed, and your parents believed, to be able to give you a better life, but instead exposed you to horrors no child should ever have to endure.

It is no wonder, so many of you say that when you went into the “home” you felt you were going out of the frying pan into the fire.

Today I want you to know we admire you, we believe you, we love you.

You experienced so many horrors it would be natural to bury their memory, too painful to recall.

But bravely you have climbed down that dark well of bitter memory and brought back into the light the stories of your life – stories that must be told and re-told and never ever forgotten.

And by having the courage to do this, having the courage to stand up and tell your stories, you have done more than paint a picture of an era of neglect, exploitation, cruelty and abuse.

You have, as Joanna Penglase reminds us, also set up a window through which we can see things far off and very close.

Through your story we look straight into our own hearts as well.

At the beginning of the Senate Committee’s “Forgotten Children” Report there is a quotation of Nelson Mandela.

“Any nation that does not care for and protect all of its children does not deserve to be called a nation.”

And this nation did not care enough for you. It did not protect you as it should. And that is why we are apologising today.

Through your story we see our own failings as a nation – our own failings as people.

Mandela calls on us to care and protect all of our nation’s children. Not just our own children, not just children we find agreeable or talented or well behaved – but all of our nation’s children.

And just as we ask ourselves whether in different circumstances we too could have spent our childhood in a “home”, as you did, so we should ask ourselves whether we too could have neglected you and abused you as others did.

Or could we have been a Minister, a Bishop or a member of a worthy charity committee that presided over these homes, but did not know, or perhaps did not want to know of the neglect and the abuse that you were suffering.

Those homes are long closed and they will never re-open. But when we hear a child scream in pain in the next apartment, or we see a little boy at school with bruises, or a little girl who seems sleepless and withdrawn – do we say: it’s none of our business?

Only a few weeks ago I met the chief executive of NAPCAN, the National Association for the Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect.

NAPCAN is campaigning to raise awareness of, and therefore prevent, child abuse and neglect. We met at the Benevolent Society’s Scarba House, at Bondi, in my electorate.

There are a group of dedicated workers there supporting families where children are at risk of neglect, supporting families so that they can stay together.

They are doing their utmost to keep children together with their mothers and their fathers – helping to support some of the 30,000 children who are currently today subject to child protection orders.

It is great work they are doing – but Scarba House has another story to tell.

Fifty two years ago there was no support for single mothers deserted, abused by their husbands and so often abandoned by their husbands and by society, those mothers lost their children.

One of those children was Pippa Corbett – she was eight. She had a little sister and a little brother. She told her story to the Senate Inquiry.

Pipa wrote: “We were put into Scarba House in Wellington Street, Bondi. It was a hellhole. My brother – he was two months old – was put into a separate area away from us. I could only watch him from behind a glass window lying in a cot. He was never held or picked up and I used to yell “give me my brother” constantly and they belted me with a switch…”

But the walls of these places have neither ears nor mouths. Only people can speak, and you have done so, courageously and especially through the work of your advocacy associations, including: the Care Leavers Australia Network; the International Association of Former Child Migrants and Their Families; the Alliance for Forgotten Australians – without your tenacity and persistence there would have been no Senate Inquiry and certainly no apology today – and can I add to the Prime Minister’s thanks to those members of the Senate Inquiry, but in particular to you, Senator Murray.

Last week, I visited the museum at CLAN’s office in Sydney and I saw there a little suitcase, it belonged to a boy called Peter Hicks.

The inside lid of the suitcase was plastered with the marks of old sticky tape Peter had used to attach, very carefully, the lists of the contents of his suitcase – a pair of socks, a pair of underpants, a pair of shorts, a shirt – this was all his worldly possessions.

Peter had been given the suitcase when he was four years old. Each year he would pack his belongings excitedly at the Melbourne City Mission in Brunswick and later the Gordon Home for Boys, and he would be escorted outside the gates of the home, where he would make the trip to High Street, Thornbury, to spend four or five weeks over Christmas with his “holiday parents“, Mr and Mrs Wright.

This was the one special opportunity to sample, if only briefly, the family life he imagined other kids might enjoy.

The suitcase, this little battered suitcase, was Peter’s one passport to a life beyond the grim orphanage in which he had found himself at only 14 months of age.

Fortunately for Peter, his holiday parents, Mr and Mrs Wright, were the same parents every summer. Even attending Peter’s marriage to Carol, standing in the place of parents Peter would never really know.

Like so many care leavers and child migrants, there is much about his childhood Peter cannot forget or forgive from his time at the Gordon Boys Home: the violent assaults; the degrading abuses; the loss of innocence – where marginalised children like Peter were brutalised, and used as child labour, under the guise of safeguarding their faith, or protecting them from “moral danger”.

Peter writes “you taught me nothing about love as a child only cruelty and low self esteem”.

In these institutions, children were not allowed to talk during meal times, or allowed to sustain each other through friendship, but especially they were denied the friendship of kinship.

Peter, bearing the tragedy of not knowing his parents, was then split apart from his own brothers – a story that is as you know as cruel as it was common.

But, perhaps most of all, the greatest tragedy was never really knowing his mother. A tragedy faced by so many of you the former child migrants and children who grew up in these homes.

With no belongings, nowhere to sleep, and completely cut off from his family, Peter tried to find the one person whose love and affection all children desire – that of their mother.

He wrote away, seeking answers, but he received an abrupt and business like response from the Police saying ‘they didn’t do that sort of thing’.

At the age of 40, he received a call out of the blue. A woman was in hospital, and had requested he come. He wasn’t told why. Peter’s mother was on her deathbed. Six weeks later, she died of cancer. For only six weeks out of his 56 years, Peter got to know his mum. Peter is with us here today.

Stories like Peter’s are a savage indictment on our society. But we must tell them.

And here in Australia’s Parliament House, we stand before you, the Forgotten but now Remembered Australians and the former child migrants to say on behalf of all Australians that we as a nation are sorry.

I hope, as do we all, that this apology helps restore dignity and respect. We are apologising for failing to believe you, for failing to protect you.

To those children whose brutal experiences in out of home care has irreparably damaged you – we apologise, and we are sorry.

To the former child migrants, who came to Australia from a home far away, lead to believe this land would be a new beginning, when only to find it was not a beginning, but an end, an end of innocence – we apologise and we are sorry.

To the mothers who lost the maternal right to love and care for their child – we apologise, and we are sorry.

To those who died hearts broken from a life of pain and hurt all too often in despair taking their own life – we apologise, and we are sorry.

To the families whose lives have been impacted by the failure to properly protect and care for your parents, grandparents, husbands and wives, when they were just little children – we apologise and we are sorry.

We are sorry because none of us can give back what was taken. We are sorry because not one of us here today has the power to undo the damage done. We are sorry because we cannot restore to you the one thing to which all children should be entitled as a basic right – a safe and beloved childhood. We are sorry because, across the generations, the system failed you; the nation failed you, by looking the other way.

As custodians of your interests, this Parliament, and other parliaments around the country and indeed across the world, allowed some of the youngest and most vulnerable of our citizens to be exposed to dangers and hardships to which no child should ever be exposed.

Through our failure to be more vigilant, to be more caring, we burdened young lives with fear and anguish – and in the worst cases, with the misery and the torment of physical, sexual and mental abuse.

Now we recognise the different experiences of each and every single child growing up in institutionalised care. Each of you has a story to tell of your own personal experiences and each story has enormous value and I welcome the initiatives the Prime Minister has announced today, all of them, but let me particularly note the support he has given to you to tell your story so that just as you will no longer be forgotten, you will be remembered and your stories will be remembered and never forgotten.

We know you tried to run away, all those years ago, and we apologise for never stopping to ask the question – why?

Thank you, all of you who have been able to share your memories, however painful to ensure this part of our nation’s story is told and remembered. We acknowledge, we admire your courage and your honesty. We know that for many of you this was the first time these awful events had been discussed with your own families and your own children. Know this: we believe you.

You were failed by the system of care. For far too long, your stories were not believed, when they should have been and for that too, we apologise and we are sorry.

They are the stories we need to tell today, to help others to understand that journey because each and every one of you here today are survivors.

We recognise those ‘survivors’ who have had happy adult lives, have raised their own families, and have succeeded in overcoming their painful pasts.

Yet as much as we admire the resilience and the bravery of those who have managed so well, to put it behind them, we must also be unstinting in our profound sympathy, compassion, respect and understanding for those for whom the scars inflicted by years of trauma may never heal.

For those who have suffered decades of grief, haunted by your childhood – emotionally paralysed and unable to move forward, today I hope you can take the first step forward because you are not to blame. It was governments, churches and charities that failed you – and for this, we are truly sorry.

I hope that this apology, too late in coming, helps you to find peace.

And more than that, let us resolve that here today we will be forever vigilant in the protection of our nation’s children – our children, your children, all of Australia’s children.

Thank you very much.