Spanish flu

- Mar 12, 2021

- In Features

A century before COVID-19, Spanish flu tore through the world’s population threatening children in institutional care in Australia.

A year after COVID-19 first made it to our shores, we look back on a previous pandemic, and the devastating impact it had on children in institutional care.

In 1919, ‘Spanish flu’ was brought to Australia by soldiers returning from WWI, many dodging quarantine, and spread quickly through the population.

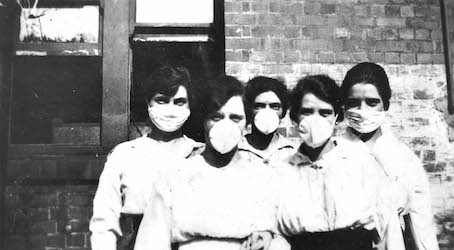

Australia’s Commonwealth Serum Laboratories developed an experimental vaccine that may have been of some benefit in controlling secondary infection, but was useless against the virus. Without an effective vaccine, and with children crowded into orphanages, it wasn’t long until the virus overtook institutions like St Vincent de Paul Orphanage in Melbourne.

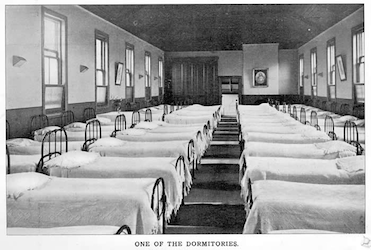

St Vincent de Paul Orphanage

In the first four days, sixty-five were infected, including one of the Christian Brothers working at the Orphanage, which was then converted into a hospital complete with a makeshift mortuary. On the fifth day, another 50 were diagnosed.

In parallels with the COVID-19 virus, nurses became exhausted from overwork, or became ill themselves, impacting on the childrens’ care. Forty percent of Australia’s population were infected with the virus now impacting heavily on the children at the Orphanage, which was without adequate funds or staff to care for them. Of Australia’s population of five million, up to 15 000 would die in what is known as one of history’s most deadly events.

As the plight of the children became known, donations of food, clothing and cash flooded in from all over Australia. The Red Cross provided assistance with the hospital, providing stretchers and bedding, and an additional 17 Sisters and 13 Brothers were sent to help nurse the sick. Another Brother was diagnosed. The children continued to fall ill.

By March 1919, after a month of battling the virus, the Orphanage was declared influenza-free. All but one of the children had become ill. All the children survived. The mortuary was packed away, having never been used.

St Vincent de Paul Orphanage in 1930

The Spanish flu left many children orphaned, many of whom were then sent to institutions that had been ravaged by the influenza due to crowding, nutrition, and standards of care.

It wasn’t until the 1960’s that Australia finally began the move away from institutional care to fostering and smaller group houses, much later than other countries in the Commonwealth.

The records from St Vincent de Paul Orphanage are available through MacKillop Family Services Records, and The Public Record Office Victoria.

Further reading:

Looking back: The ‘Spanish Flu’ pandemic…

The virus that threatened to destroy a Melbourne orphanage

A century after the Spanish flu, are we ready for another pandemic?

Opinion | Dr David Williams reflects on how the city dealt with Spanish flu in 1919

My mother, the Spanish flu orphan

A short history of vaccination campaigns in Australia and what we might expect with COVID-19

Frank Golding

March 12, 2021 1:11 pmThe influenza pandemic was certainly a problem for children in orphanages, but it was also a problem for many who served in the First World War. Bertie Cooper and Ivo Bibby were two former Ballarat Orphanage boys who were extra keen to be involved in the War, like the 100 or so other boys from the Orphanage. The problem was that Bertie and Ivo were too young. It was not until the War was almost finished that they were finally accepted—now both just 19.

Bertie was among the 900 reinforcements aboard the troopship Boonah which sailed from Adelaide on 22 October 1918, bound for the Middle East. When the ship arrived at Durban, South Africa, on 16 November, Bertie was told that the Armistice had been signed five days earlier. He would never set foot on foreign soil. ‘Spanish’ influenza was rampant in Durban and the ship was quarantined and then sent back to Australia. During the journey home the dreaded virus erupted on board with devastating results. Hundreds were stricken and 27 soldiers and four nurses later died (Darroch, Ian, The Boonah Tragedy, Access Press, Bassendean, 2006). Bertie was bitterly disappointed that he did not make it to the front, but he could say he had been with some who died for Australia.

Meanwhile, Ivo Bibby was aboard the troopship Carpentaria when it set sail from Sydney on 7 November 1918 bound for Europe via the Panama Canal. Just off Auckland, the news of the Armistice came through by wireless. Like Bertie, Ivo never set foot on foreign soil because Auckland was also hit by the deadly influenza epidemic (Adelaide Advertiser, 19/11/1918; 6; 27/11/1918: 7). The troops were transferred at sea to the SS Riverina to return to Sydney. After a short period in quarantine, the Riverina was declared clean and the troops disembarked on 28 November. Discharged in time for Christmas, Ivo returned to live with another former Ballarat Orphanage boy in a boarding house in Footscray.

Both boy-soldiers had been in mortal danger, not from the Germans, but from the deadly influenza epidemic.